The Taking of Seville

Brigadier-General Downie was next in Cadiz, where he sought and was given permission to join Field-Marshal Don John de las Cruz Mourgeon as second in command in an expedition to relieve Seville. The 4000 strong expedition landed at the port of Huelva on 11 August and was reinforced by 1600 elite British troops under the charge of Colonel Skerrett. The combined force captured Sanlucar la Mayor on 25 August 1812 but paused before advancing toward Seville because of a strong build up of French troops in the city, with more troops on the march towards Seville from Cadiz. However, instead of defending the city, Soult made the strange decision to withdraw his own force, leaving behind a rearguard to occupy the outworks of the city and to await the arrival of the reinforcements from Cadiz. They left accompanied by a vaste horde of Spanish refugees fleeing with 'the spoils of three years of tyrannous misrule in Andalucia.' [Oman, p 540]

Cruz Mourgeon and Skerrett took advantage of the temporary inability of the French to defend the long perimeter of Seville and on 27 August they entered Triana, on the West side of the Canal de Alfonso XIII, across which was the bridge leading into the city. Oman [page 541] picks up the story:

The bridge had been barricaded, part of its planks had been pulled up, and artillery had been trained on it from the farther side. Notwithstanding these obstacles the Spaniards attacked it ; the well-known Irish [sic] adventurer Colonel Downie charged three times at the head of his Estremaduran Legion. Repelled twice by the heavy fire, he reached the barricade at the third assault, and leaped his horse over the cut which the French had made in front of it, but found himself alone within the work, and was bayoneted and made prisoner.

Toreno (iii. p. 151) and other historians tell the tale how Downie, finding that none of his men had followed him, though they had reached the other side of the cut, flung back to them his sword, which was the rapier of the Conquistador Pizarro, presented to him by a descendant of that great adventurer. It was caught and saved, and he recovered it, for he was left behind by the French a few miles from Seville, because of his wounds. They stripped him and left him by the wayside, where he was found and cared for by the pursuing Spaniards.

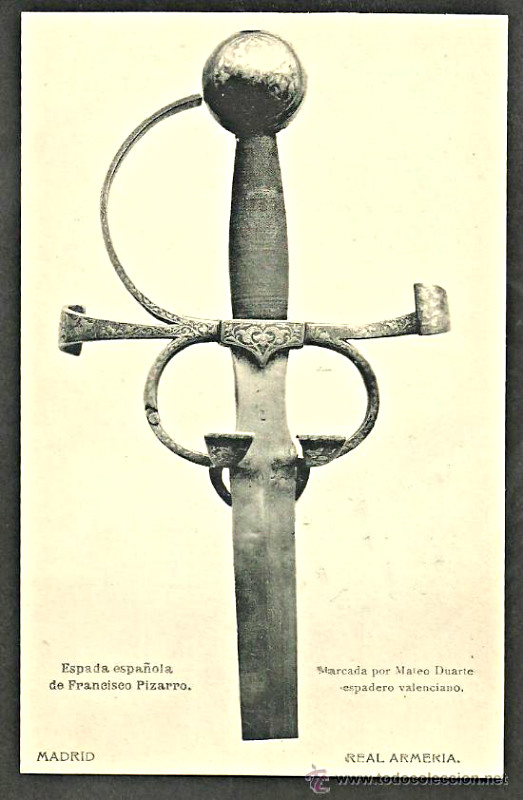

The sword of Pizarro in Real Armeria de Madrid

Following the liberation of Seville, this item appeared in the Caledonian Mercury of 22 June 1812:

The Marchioness of Conquisa, according to a Spanish paper, has presented to Brigadier Downie, commandant of the Estremadura legion, the sword of Pizarro, the conqueror of Peru (whose descendant she is) which had been preserved in her family for a number of years.

The newspaper may have mistaken the gender of the Marchioness, because Spanish accounts refer to a male descendant of Pizarro who presented it saying that he was too old to fight. There is a sword in the Real Armeria de Madrid which is said to be the sword of Francisco Pizarro, conqueror of Peru, though the catalogue states that the provenance of this sword is unknown. This sword appears to be very similar to the one held by John Downie in his portrait in the Museo de las Cortes in Cadiz presented to Brigadier Downie and Badcock [p113] writing in the 1830s refers to this sword as being the one presented to Sir John Downie and which he threw back amongst his troops before being captured at the bridge of Triana.

The biography of Brigadier-General Downie has this to say about his part in the liberation of Seville:

The last affair of importance in which General Downie signalized himself was in driving the French out of Seville. His legion was twice repulsed in their attempts to force the bridge, and their brave commander each time wounded. On the third attack, and just as he had cleared the chasm made by the enemy in the bridge of Seville, to aid their defences, he received a severe wound by a grape shot, on the face and head, which shattered the cheek bone, and totally destroyed the vision of his right eye. He was so much stunned as to fall from his horse, and, upon coming to his recollection, he found' himself surrounded by the enemy, and taken prisoner. But even in this trying situation, and suffering from the pain of numerous wounds, his presence of mind did not forsake him, and, by a prodigious effort, he succeeded in throwing his sword (the same which once graced, the thigh of the renowned Pizarro, and presented by his descendant, the Marchioness de Couquisto, to General Downie, as most worthy to wear it), amongst his own people, who still, notwithstanding the fall of their heroic leader, continued to force the bridge, and finally succeeded in dislodging the enemy.By the directions of General Villatte, the French Commander, General Downie was carried 40 miles to the rear, and most barbaronsly treated, being fastened to the carriage of a gun, and in that situation dragged along for a considerable distance. At length he was left in a hut, as the enemy did not expect him to survive. However, they had the precaution to take his parole of honour not to serve again until regularly exchanged, which has been recently effected in a manner highly flattering and honourable to this gallant officer.

After a period of recovery, General Downie returned to Britain to receive many honours.

Return to Britain in late 1812

Bibliography

Badcock, Lieut.-Col Lovell (1835) A Journal kept in Spain and Portugal, during the Years 1832, 1833, & 1834. London: Richard Bentley

Gurwood, John, comp (1837-8) The dispatches of Field Marshall the Duke of Wellington during his various campaigns in India, Denmark, Portugal, Spain, the Low Countries, and France, from 1799 to 1818. Vol. 8. London, J. Murray

Oman, Charles (1914). A History of the Peninsular War Vol. V Oct. 1811—Aug. 31, 1812. Oxford, Clarendon Press. Online at https://ia800308.us.archive.org/26/items/historyofpeninsu05oman/historyofpeninsu05oman.pdf viewed 22 October 2019.

Toreno, Count of (1835-7) Historia del Levantamiento, Guerra, y Revolucion de Espana (History of the Insurrection, War, and Revolution of Spain) Vol. III. Madrid.